Features

Job Cuts

Workforce Statistics

More than one million jobs last in March, unemployment rate jumps to 7.8 per cent

By Talent Canada Staff/Statistics Canada

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty Images Statistics Canada says the economy lost more than one million jobs in March as the COVID-19 crisis began to take hold, sending the unemployment rate higher to 7.8 per cent.

Economists warn the numbers are likely to be even worse when the agency starts collecting April job figures, with millions more Canadians now receiving emergency federal aid.

The 2.2 percentage-point increase is the biggest monthly change in the national unemployment rate over the last 40-plus years of comparable data and brings the rate to a level not seen since October 2010.

Statistics Canada retooled some of its usual measures of counting employed, unemployed and “not in the labour force” to better gauge the effects of COVID-19 on the job market, which has been swift and harsh.

The number of people considered unemployed rose by 413,000 between February and March, almost all of it fuelled by temporary layoffs, meaning workers expected their jobs back in six months.

The number of people who didn’t work any hours during the week of the labour force survey increased by 1.3 million, the national statistics office says, while the number who worked less than half of their usual hours increased by 800,000.

Statistics Canada says those changes in hours can all be attributed to COVID-19, which has led governments to order businesses to close and workers to stay at home to slow the spread of the pandemic.

It also warned that the number of people absent from work for a full week who weren’t paid — which hit a seasonally adjusted rate of 55.8 per cent — “may be an indication of future job losses.”

All told, Statistics Canada says some 3.1 million Canadians either lost their jobs or had their hours slashed last month due to COVID-19.

Diving into the numbers

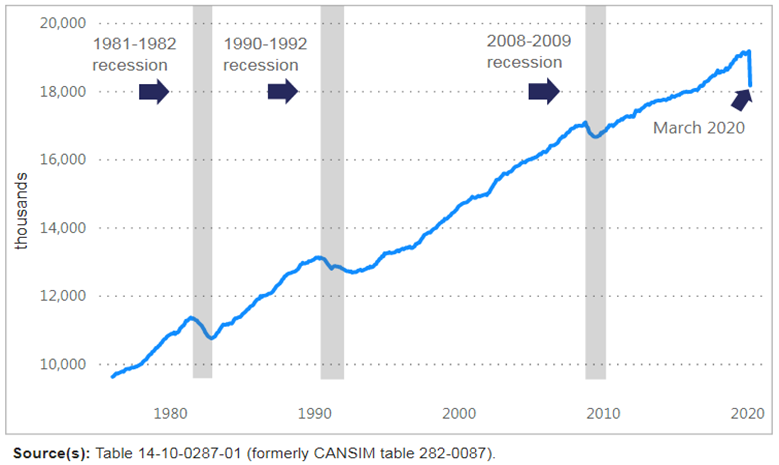

It is expected that the sudden employment decline observed in March will have a significant effect on the performance of the Canadian economy over the coming months, according to Statistics Canada. The employment decline in March was larger than in any of three significant recessions experienced since 1980.

Provincially, employment fell in all provinces, with Ontario (down 403,000 or 5.3 per cent), Quebec (down 264,000 or six per cent), British Columbia (down 132,000 or 5.2 per cent) and Alberta (down 117,000 or five per cent) reporting the largest declines.

Large movements out of employment

In any month, the net change in employment is the result of the difference between the number of people leaving employment and the number becoming newly-employed.

In March, most of the employment change was the result of people leaving employment. Both the number of people moving from employment to unemployment (506,000) and those moving from employed to not in the labour force (515,000) increased.

Temporary job losses

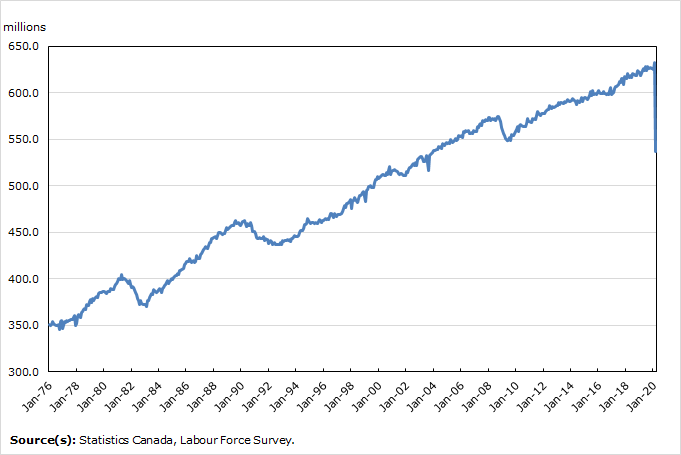

The number of people who were unemployed increased by 413,000 (up 36.4 per cent) from February to March, the largest monthly change since comparable data became available in 1976. Almost all of the increase in unemployment was due to temporary layoffs, meaning that workers expected to return to their job within six months.

The unemployment rate increased 2.2 percentage points to 7.8 per cent in March. This was the largest one-month increase on record, and brought the rate to a level last observed in October 2010.

The unemployment rate increased in all provinces except Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island. The largest increases were in Quebec (up 3.6 percentage points to 8.1 per cent), British Columbia (up 2.2 percentage points to 7.2 per cent) and Ontario (up 2.1 percentage points to 7.6 per cent).

In March, the number of people who were out of the labour force — that is, those who were neither employed nor unemployed — increased by 644,000.

Of those not in the labour force, 219,000 had worked recently and wanted a job but did not search for one, an increase of 193,000 (up 743 per cent). Because they had not looked for work and they were not temporarily laid off, these people are not counted as unemployed. Since historically the number of people in this group is generally very small and stable, the full monthly increase can be reasonably attributed to COVID-19.

Increased absences show impacts of COVID-19

There were 1.3 million Canadians who were away from work for the full week of March 15 to 21, for reasons that can likely be attributed to COVID-19, including ‘business conditions’ and ‘other reasons’ but excluding reasons such as ‘vacation’; ‘labour dispute’; ‘maternity leave’; ‘holiday’; and ‘weather’.

The number of Canadians who were employed but who worked less than half their usual hours due to ‘business conditions’ or ‘other reasons’ increased 800,000 in March.

When these absences are included, the total number of people who missed all or part of their week increased to 2.1 million and the total number of Canadians who were affected by either job loss or reduced hours was 3.1 million.

For employees who were absent from a job for the full week, about 55.8% were not paid (not adjusted for seasonality). The number of people who were absent all week without pay may be an indication of future job losses. The Labour Force Survey does not collect information on whether people who are absent for part of the week were paid for the hours they did not work.

More hours lost than during 1998 Ice Storm

The Labour Force Survey began measuring hours lost in 1997. Since then, the closest comparison to the sudden decline in economic activity and employment observed in March 2020 has been the 1998 ice storm, which caused business closures in parts of Quebec and Ontario, and resulted in an estimated 166,000 people across Canada losing all or the majority of their hours worked. The increase in absences the week of March 15 to 21 was more than eight times greater than that observed in 1998.

COVID-19 creates a complex picture: Not working, but not unemployed

The unemployment rate is the number of people unemployed as a proportion of the total labour force (employed plus unemployed). In March, the unemployment rate increased by 2.2 percentage points to 7.8 per cent, the largest one-month increase since comparable data became available in 1976.

In March, 219,000 people were not in the labour force but had worked earlier in March and still wanted a job. They were not counted as unemployed because they did not look for a job, presumably because of ongoing business shutdowns and the requirement to socially isolate.

If this group were counted as unemployed, the adjusted unemployment rate would be 8.9 per cent.

In March, the “recent labour underutilization rate” was 23 per cent, meaning about one-quarter of the potential labour force was fully or partially underutilized. In comparison, this rate was 12.8 per cent at the peak of the 2008/2009 recession, highlighting the depth of the impact of COVID-19 on the Canadian labour market.

The “recent labour underutilization rate” is calculated by combining all those who were unemployed with those who recently worked and wanted a job but did not meet the definition of unemployed; and those who remained employed but lost all or the majority of their usual work hours.

Most employment losses in the private sector; small declines among self-employed

Employment decreased more sharply in March among employees in the private sector (down 830,200 or 6.7 per cent) than in the public sector (down 144,600 or 3.7 per cent).

The number of self-employed workers decreased relatively little in March (down 1.2 per cent or 35,900), and was virtually unchanged compared with 12 months earlier. The number of own-account self-employed workers with no employees increased by 1.2 per cent in March (not adjusted for seasonality).

Most of this increase was due to an increase in the healthcare and social assistance industry (up 16.7 per cent), which offset declines in several other industries. At the onset of a sudden labour market shock, self-employed workers are likely to continue to report an attachment to their business, even as business conditions deteriorate.

Greatest employment declines among youth

Among youth aged 15 to 24, employment decreased by 392,500 (down 15.4 per cent) in March, the fastest rate of decline across the three main age groups. The decrease was almost entirely in part-time work, and brought the employment rate for youth to 49.1 per cent, the lowest on record using comparable data beginning in 1976.

About two-thirds of youth are students, and employment fell more sharply among those enrolled in school (down 31.6 per cent), than among non-students (down 1.8 per cent), unadjusted for seasonality. Students are also more likely to work in the accommodation and food services industry, which had the largest declines overall.

Approximately 20 per cent of employed youth lost all or the majority of their usual hours.

Unemployment for youth increased by 145,300 (up 49.7 per cent) in March, bringing their unemployment rate up 6.5 percentage points to 16.8 per cent, the highest rate for this group since June 1997. An additional 88,400 (up 1892.4 per cent) youth wanted work in March but did not search due to reasons related to COVID-19 (not adjusted for seasonality). Including that group would result in a supplemental youth unemployment rate of 20.7 per cent (not adjusted for seasonality).

In core-age population, more losses among women than men

Among people in the core working ages of 25 to 54, the monthly decline in employment for women (down 298,500 or 5.0 per cent) was more than twice that of men (down 127,600 or 2.0 per cent). Nearly half of the decrease among women was from part-time employment (down 144,100 or 14.0 per cent).

The number of core-aged women (25 to 54 years) who lost all or the majority of their usual hours increased by 885,000 (up 433.3 per cent) from February to March (not adjusted for seasonality). This represents 19.2 per cent of employed women in this age group. For employed men in this age group, there was an increase of 637,000 who lost all or the majority of their usual hours (up 280 per cent), which resulted in 13.9 per cent of this group being affected.

There were 162,000 (up 55.8 per cent) more core-aged women unemployed in March than in February, raising their unemployment rate 2.8 percentage points to 7.4 per cent. For men in this age group, unemployment increased by 71,300 (up 21.8 per cent) bringing the rate up 1.1 percentage points to 5.9 per cent.

Of all workers in this age group who recently worked and wanted a job but did not search in March, approximately two-thirds (67.0 per cent or 99,400) were women (not adjusted for seasonality). Including this group of marginally attached workers with the unemployed would result in a supplemental unemployment rate for women of 8.7 per cent, and 7.6 per cent for men (not adjusted for seasonality).

Largest employment losses among vulnerable workers

In general, workers in less secure, lower-quality jobs, were more likely to see employment losses in March.

The number of employees in temporary jobs decreased by 14.5 per cent (down 274,900) compared with a decline of 5.3 per cent (down 749,500) among employees with permanent jobs (unadjusted for seasonality). Decreases were observed across all types of temporary work, led by those in casual employment (down 23.5 per cent or 136,000). There were five per cent fewer temporary workers with a term or contract position.

Temporary employees were more likely to lose all or the majority of their usual work hours (21.7 per cent) compared with permanent employees (11.6 per cent) in March, unadjusted for seasonality.

Not adjusted for seasonality, employment fell slightly more among employees not covered by a union or collective agreement (down seven per cent or 777,600), and they were more likely to lose all or a majority of their usual work hours (19 per cent). In contrast, the number of employees covered by a union or collective agreement fell by five per cent (246,900), and 13 per cent lost all or a majority of their usual hours.

Half (49.9 per cent) of the decline in employment among employees (not adjusted for seasonality) was accounted for by those earning less than two-thirds of the 2019 median hourly wage. Employment for this group declined by 15.8 per cent (510,800) in March, compared with a decrease of four per cent (513,600) among higher-paid employees. The number of low-wage employees who lost all or the majority of their hours increased by 545.5 per cent (496,000) in March, compared with an increase of 444.2 per cent (1,072,000) for higher-wage workers.

Multiple jobholding declines

The number of workers holding more than one job at the same time decreased by 25.6 per cent (down 283,200) in March (unadjusted for seasonality).

As seen for total employment, youth (down 33.6 per cent or 44,900) and core-aged women (down 30.5 per cent or 127,200) saw the most notable declines in holding multiple jobs. The share of workers holding more than one job declined from 5.8 per cent to 4.5 per cent, a rate last seen consistently in the late 1980s. If workers are holding multiple jobs for financial reasons, this decline could compound the financial impact of the COVID-19 related business closures for some workers.

COVID-19 affects both family earning ability and living arrangements

The ability of Canadians to withstand the economic hardship associated with COVID-19 depends on a number of factors, including their family and living arrangements.

Employment losses in March affected a range of family types, including couple families where one or both partners may have lost their job. Between March 2019 and March 2020, the number of spouses/partners in dual-earner couples decreased, while those in single and non-earner couples increased by 918,000 (+11.7 per cent), unadjusted for seasonality.

In addition to employment impacts, directives to socially isolate at home may have affected living arrangements. A number of Canadians living alone or with non-relatives were faced with a choice to self-isolate by themselves or to move in with family members. On a year-over-year basis, unadjusted for seasonality, the total number of unattached individuals decreased by 128,000 (down 2.2 per cent), while the number of lone parents decreased by 38,000 (down 3.5 per cent). As a point of reference, the total Canadian population aged 15 and older increased by 1.6 per cent over the same period.

Largest job losses in accommodation and food services industry

The federal and provincial governments issued social distancing orders or recommendations before and during the Labour Force Survey (LFS) reference week restricting the activities of many workplaces. Government measures instated early in the LFS reference period included states of emergency, restrictions on certain business activities, and limits on the travel of non-residents into the country.

Businesses and organizations may have responded to these unprecedented instructions in a number of ways.

They could have reduced activities, resulting in a combination of reduced work hours, temporary layoffs, and permanent reductions in employment. Alternatively, they could have continued to operate as usual or continued operations with an increased reliance on telework, depending on the nature of their operations.

In March, the largest employment declines were recorded in industries which involve public-facing activities or limited ability to work from home. This includes accommodation and food services (down 23.9 per cent); information, culture and recreation (down 13.3 per cent); educational services (down 9.1 per cent); and wholesale and retail trade (down 7.2 per cent).

Smaller employment declines were observed in most other sectors, including those related to essential services, such as health care and social assistance (down four per cent). Employment was little changed in public administration; construction; and professional, scientific and technical services. An employment increase was observed in natural resources.

Even within industries which recorded the largest employment declines, not all occupations were equally affected. On average in 2019, employment in sales and service occupations represented about one-quarter of total Canadian employment, but in March 2020, these occupations accounted for 61.8 per cent of the overall employment decline in the month, dropping by an estimated 625,000.

Jobs in this occupational group are relatively low-paid, indicating that the first workers to experience job losses as a result of COVID-19 are among those least able to withstand economic hardship. In 2019, the average hourly wage rate of employees in sales and service occupations was $18.36, compared with the total employment average of $27.83.

As with employment declines, industries which involve public-facing activities or a limited ability to work from home saw the largest declines in hours worked. This includes accommodation and food services (down 41.1 per cent); information, culture and recreation (down 30.6 per cent); and educational services (down 28.8 per cent).

Overall, total hours worked decreased more in the services-producing sector (down 17.3 per cent) than in the goods-producing sector (down 8.3 per cent).

Accommodation and food services

In March, employment in accommodation and food services declined by 294,000 (23.9 per cent) on a month-over-month basis. Employment declined at a similar rate in the two sub-sectors: food services and drinking places; and accommodation services.

The March decrease is by far the largest employment variation in the sector since comparable data became available in 1976.

During the 2008/2009 recession, for example, employment in this industry declined by 5.4 per cent in the 12 months to September 2009.

In March, the number of people employed in accommodation and food services declined in all provinces, ranging from 13.5 per cent in Newfoundland and Labrador to 27.9 per cent in Alberta.

In March 2020, half of those that were still employed in the accommodation and food services sector worked 15 hours or less per week, compared with an average of approximately 25 per cent over recent years (data unadjusted for seasonality). One in four reported having worked zero hours, compared with an average of 7% over recent years. This increase in lost hours suggests that further employment losses may be observed in this sector in April. On the other hand, since the March LFS reference week, a number of restaurants have begun offering delivery and take-out services, an example of business adaptations which might partially mitigate further losses.

Information, culture and recreation

Employment in the information, culture and recreation sector decreased by 104,000 or 13.3 per cent in March, with declines observed in all provinces.

On a year-over-year basis, employment declined in performing arts, spectator sports and related industries, consistent with the cancellation or postponement of large sports and entertainment events across the country.

Educational services

Employment in educational services declined by 9.1 per cent (or 125,000) in March, the largest monthly decline in the sector since comparable data became available in 1976.

Most of the decline was observed in Quebec (73,000) and Ontario (25,000) while there were smaller declines in British Columbia, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia and Manitoba. Employment in educational services was little changed in the other three provinces. The Quebec provincial government announced the closure of all schools, universities and daycares on March 13. The government of Ontario made a similar announcement around the same time, as March break was about to begin in their province.

Compared with March 2019, declines were observed in non-professional occupations in education, such as educational support workers, while employment in professional occupations in educational services was little changed (not adjusted for seasonality). Employment declined by about 10% for those who were not covered by a collective agreement compared with about four per cent for those who were (not adjusted for seasonality). Similarly, declines were proportionally greater in small institutions and businesses (less than 500 employees) (not adjusted for seasonality).

Wholesale and retail trade

The number of people employed in wholesale and retail trade declined by 208,000 or 7.2 per cent in March.

Employment changes in subsectors reflect the need for some retail business to remain open despite widespread shutdowns and instructions to socially distance. For example, employment in subsectors related to food and beverages was relatively stable, while employment for clothing stores and other retail stores decreased.

Within wholesale and retail trade, the vast majority of the decline in employment was attributable to sales and services occupations, which represented over half of all the workers in the sector.

Declines in social assistance and gains in some health professions

In March, employment in health care and social assistance declined by 100,000 (down four per cent), led by a decline in the social assistance subsector. This subsector represents about 20 per cent of employment in the sector and includes day-care services.

Compared with March 2019, employment in professional and technical occupations in health care (except nursing) increased (not seasonally adjusted).

Natural resources

An important impact of the COVID-19 crisis is an ongoing decline in global economic activity, accompanied by decreases in the price of oil. At the beginning of the LFS reference week, the market price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate oil was about 54 per cent lower (in U.S. dollars) than at the beginning of 2020.

Despite the sharp fall in the price of oil, the number of people working in natural resources increased by 1.8 per cent month-over-month to 316,000 in March. In addition to oil and gas extraction, this sector includes forestry, fishing, mining and quarrying.

Canada-United States comparison

For comparison purposes, all indicators described below are adjusted to US concepts.

The unemployment rate in Canada increased by 2.3 percentage points to 6.9 per cent in March, compared with 4.4 per cent (up 0.9 percentage points) in the United States. At the same time, the employment rate (also referred to as employment-to-population ratio, which is the number of employed as a percentage of the population) fell by 3.3 percentage points to 59.1 per cent in Canada, while the U.S. rate declined by 1.1 percentage points to 60 per cent .

The labour-force participation rate in Canada fell to 63.5 per cent (down 1.9 percentage points), compared with 62.7 per cent in the United States (down 0.7 percentage points).

— with files from the Canadian Press

Print this page